by ALTITUDE ATHLETIC | Altitude Training Information, Hiking, Climbing and Mountaineering

Imagine your worst hangover. Dizziness, nausea, loss of appetite, the deep desire to just lay down, wherever you are, and sleep. Now, imagine that instead of waking up in your bed after a night out, you’re three quarters of the way up a 12,000 ft. mountain, pushing yourself harder than you ever have in your life. You are experiencing the early symptoms of acute mountain sickness, (or AMS), commonly known as altitude sickness.

Altitude sickness is an illness that develops when the body doesn’t have time to adapt to the decreased air pressure and oxygen levels of high altitude—defined as any area 8,000 ft. above sea level. Symptoms include dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and loss of appetite—wickedly similar to a brutal hangover.

In its most extreme cases, altitude sickness can develop into high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), an accumulation of fluid in the lungs, and high altitude cerebral oedema (HACE), swelling of the brain due to a lack of oxygen. Jon Krakauer provides a chilling description of Ngawang Topche, a Sherpa on the 1996 Everest expedition, experiencing HAPE in John Krakauer’s book Into Thin Air. “Ngawang was delirious, stumbling like a drunk, and coughing up pink, blood-laced froth.”

Don’t let this scare you off your planned trip to Kilimanjaro or Everest Base Camp, though. HAPE and HACE are extremely rare. They typically occur when people ignore the symptoms of altitude sickness and continue to physically exert themselves. Just be wary that if you let altitude sickness progress to this level of severity, it can prove fatal.

To ensure this doesn’t happen, follow these tips on how to handle altitude sickness.

Travel Slowly

We get it. You want to be the first one to the top of the mountain. But it’s not worth it if your group has to drag you back down. Don’t turn your ascent into a competition. By not giving your body enough time to adjust to the lack of oxygen you’re much more likely to experience altitude sickness.

According to contemporary research, age, sex and physical fitness have no bearing on a person’s likelihood to be afflicted by the illness. This means that even if you’re one of the fittest people on the planet you can still be affected, especially if you’re racing to the summit.

Before even starting your climb, it’s a good idea to take two to three days to acclimatize to higher altitude. Avoid flying directly into high altitude areas, though. Travel to the destination progressively, acclimatizing as you go.

During the climb, take it slow. Enjoy the view. If you’re hiking with porters or Sherpas, follow their lead. They know the mountain well and will know when it’s best to take a rest. If you’re climbing alone, don’t ascend more than 500 metres a day. After every 900 metres, or three or four days of climbing, take a rest day to avoid overexertion.

Remember, it’s not a race.

Stay hydrated and fed

Dehydration is a major cause of altitude sickness. In part, because high altitude has a diuretic effect on the body, causing you to pee…a lot. And with all the hiking you’ll be doing, you’re going to sweat out liquids fast. Take some hydration salts with you and toss a hydration pack in your bag that you can sip on during the hike. It’s better to carry too much water than not enough.

And just to clarify, no, beer doesn’t count as a liquid. Alcohol dehydrates you and can accelerate the altitude sickness. Save the liquor for the bar. Instead, bring water or sports drinks like Gatorade.

Altitude also tends to rob you of your appetite, slowing down your digestion. To have enough energy to hike each day, eat more than you feel is necessary. Oatmeal is a good idea in terms of meals, especially if you add some nuts and berries. And bring snacks for the climb. Munching on a chocolate bar along the way may give you the energy you need to make it to the summit.

Treat Symptoms immediately

As mentioned earlier, if not treated, altitude sickness can evolve into worse illnesses like HAPE and HACE. If you are feeling the onset of symptoms, stop and rest. Wait a day or two until the symptoms have completely receded before continuing to climb.

Proactively, you can take Diamox one to two days before starting your climb. The medication reduces symptoms and eases your adjustment to altitude. If you’re still feeling the effects while climbing, try combatting headaches with ibuprofen and Tylenol. And promethazine can work wonders when feeling sick.

If you’re still exhibiting symptoms after 24 hours, turn around and start to descend. Once down at the base, the symptoms should dispel after two to three days. Don’t try ascending to high altitude again until the symptoms are completely gone.

Train at Altitude

Before leaving for an expedition, mountaineers can pre-acclimate and prepare for high altitudes by sleeping and exercising at simulated altitude. This is a great option if you live at sea-level and can’t easily access the mountains.

Simulated altitude training is exercising in or breathing air with less oxygen to replicate the thinner air you find up in the mountains. Simulated altitude is created by decreasing the percentage of oxygen in the air below 20.9% oxygen (the amount of oxygen in the air at sea-level). There are two strategies for altitude training: Live High, Train Low and Intermittent Hypoxic Training. Both methods have been shown to improve performance in recreational and professional athletes, and those travelling to high altitudes.

Live High, Train Low

Doing sedentary tasks at altitude for longer durations, i.e “Living High”, while training at a lower level, can stimulate erythropoiesis (the process that produces red blood cells).

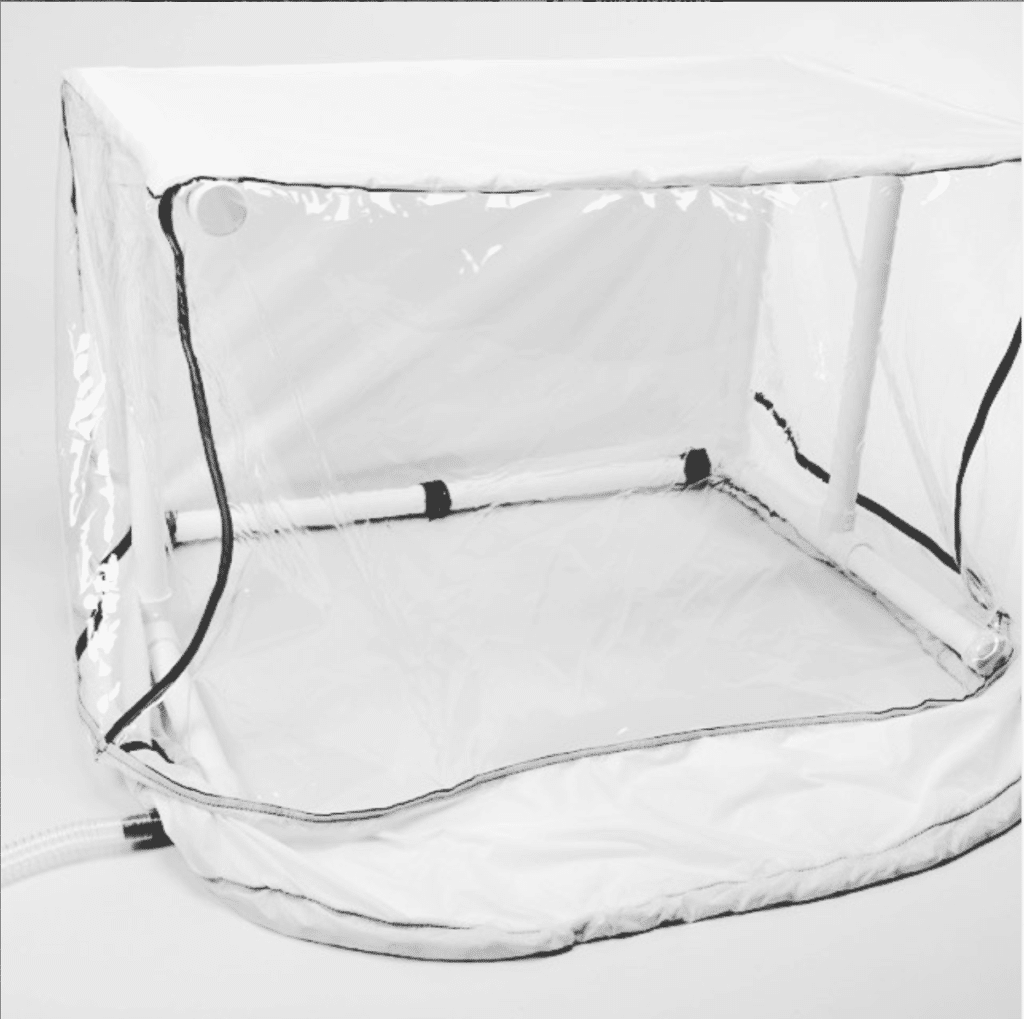

Sleep tents and larger altitude tents can be set up at home, so you can get 6+ hours of high-altitude exposure and then be back down to sea-level in seconds. Simulated altitude training can lower the age of red blood cells and increase hemoglobin mass (hemoglobin is an oxygen-carrying protein). These changes in the blood can help reduce and prevent symptoms of altitude sickness.

Intermittent Hypoxic Training

Intermittent Hypoxic Training (IHT) is living at sea-level and exercising at altitude. If you’ve got a stationary bike or treadmill at home, you can use a simulated altitude training mask to breath hypoxic air while you’re training. Otherwise, there are special gyms that can actually simulate altitude with no masks needed.

Finally, if you’re experiencing symptoms – tell someone. Your travel companions are there to help and will have clearer heads to assess the situation.

While it is a hindrance, if you monitor and treat the symptoms appropriately, altitude sickness should not be the reason you miss making it to the summit.

by ALTITUDE ATHLETIC | Altitude Training Information, General Fitness

Altitude training has been around for a while – ever since the 1968 Mexico Olympics. Despite its long history, it remains relatively unknown, especially here in North America. This is because altitude training has been used only exclusively by the pros. Only recently has the technology become more accessible to everyday athletes. Because of how elusive it is, we have come across some misconceptions about altitude training. Here are 4 of the most common ones we’ve heard:

1. It’s only for people who are planning to race at altitude

No, altitude training is not just for people competing at altitude. It’s also for people looking to improve their athletic performance at sea level, specifically increase their VO2 max, aerobic capacity and power output.

Look at it like resistance training, but for your endurance. Reducing the oxygen percentage in the room is like adding resistance to your workout. And building that kind of training into your program will improve (or at the very least, maintain) performance at any elevation.

2. Altitude training is dangerous

We commonly get the question – “Is altitude training safe? There are risks associated with any form of physical activity – whether it be hot yoga, a high intensity spin class, or a run around the neighborhood. The same goes for training in a simulated altitude environment. To reduce risk as much as possible – members are assessed and screened before entering the altitude room. During training, members are given carefully regulated programs based on their conditioning. Additionally, members are always under supervision from trained coaches. Heart rate monitors and pulse oximeters are used regularly to monitor exertion.

Of course, not all forms of exercise are safe for everybody. And altitude training isn’t recommended for people who are pregnant, have breathing problems like asthma, have high blood pressure or other serious medical issues.

3. But I’ll lose strength and power exercising at altitude

Training in reduced oxygen typically means you are unable to reach the same levels of ‘intensity’ as you can at sea level. It is this stress of hypoxia on the body that stimulates it to be more efficient in using oxygen and providing energy to active muscles, improving aerobic conditioning and endurance. Continuous exposure to high altitude will cause you to lose power. But, when you combine simulated altitude training sessions (2-3 per week) with your regular strength and power sessions at sea level – you can maintain, and actually boost, your strength and power levels no problem.

4. I’ve heard that you are supposed to sleep in an altitude tent. Why exercise?

Altitude tents are designed for the “live high, train low” model. This method of training (sleeping at altitude) is commonly used by athletes to increase their red blood cell count and improve overall performance.

For those of us living at sea level, and who aren’t professional athletes – altitude tents can become impractical. We don’t have the benefit of naturally ‘living high’ and it can be hard to get the most out of an altitude tent – which you should be using for 4 weeks, 16 hours/day while maintaining training. See here.

A great alternative is simulated altitude training, which follows the “live low, train high” model. You already live low, and perhaps mostly compete low. Training high gets the job done quicker (2-3 sessions per week is usually recommended) and it’s much easier to convince your partner about heading to the gym than sleeping in a tent.

_________________________________________________________

So now hopefully you can answer the question “Is altitude training safe?” And if you have any other questions about altitude training and memberships at Altitude, please contact us at info@altitudeathletictraining.com or book a coach consult here.

Follow us on Instagram and Facebook for the latest updates on Altitude Athletic.